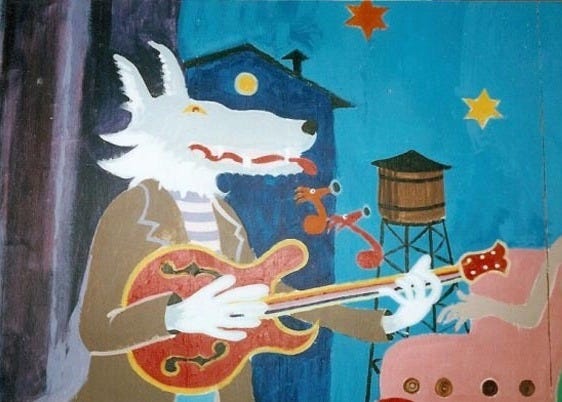

The regular canine characters that crop up in Michael Hurley’s songs, album artwork and comic books might well be the collie dogs of his childhood – Boone and Jocko – along with a supporting cast of wild wolves and voracious werewolves. But if Hurley is the pooch alter-ego called Snock that he thinks he is – and, what with his ravenous fixation on food and sex, rapid fluctuations in mood between tail-wagging cheer and mopiness, and eternally juvenile personality, I’m inclined to agree – he’s certainly no working dog. He’s a sleepy mutt, snoozing all day on the porch and letting the sheep do whatever they damn well please. Musically speaking, this works to his favour, and his best songs have a kind of concentrated energy that must require enormous amounts of napping in advance of the creative process. They can be steadily meandering songs, best represented mentally as long and satisfying stretches of the paws while resting on the banks of a river. Or occasionally they can be charged with a kind of spontaneous post-nap energy, with these numbers usually accompanied by sprightly fiddling and strained vocals. As music critic Robert Christgau puts it, “When Hurley is good, his tunes snake up on you. When he’s not, they snail right past, disappearing forever behind that cabbage leaf there”. I’d go one step further, and argue that his snakiest tunes require the energy of three songs’ worth of material, meaning that for every memorable snake on an album there must be two forgettable snails. This could go some way to explain why Hurley has brilliant tunes and underwhelming albums.

But while his songs are usually sleepy in feel, his words are often peculiarly alert. He takes the song-writing mannerisms and antiquated phrases of the early blues and folk greats from Jelly Roll Morton to Pink Anderson, and adds his own off-kilter, goofball-folkie personality to them. He comes to his songs from a similar (albeit white) world to his southern predecessors; a world of poverty contrasting with natural beauty, with an emphasis on pleasures hard to come by. He’s hungry. He’s perverted. He’s drunk and starry-eyed. He’s actually kind of pathetic. I bet he never does the dishes. But he’s loveable all the same, partly because he’s a convincing storyteller, but maybe primarily because there is always a sense of companionship with his audience at the heart of things. “I’m playing to the nice nightlife type”, he says in almost every interview. His latest album begins with the joyful words, “Did you ever leave Nelsonville with a broken heart? / Did you ever leave Woodstock falling apart?”, in doing so establishing the folk festival as a place for spiritual healing. He knows that the strength of music is its capacity for hope and joy, even something approaching awe, and that his audience finds this as heartening a thing as he does.

If, like me, you’re one of the nice nightlife types that he’s playing to, I hope you enjoy the Best of Michael Hurley. All snakes, no snails.